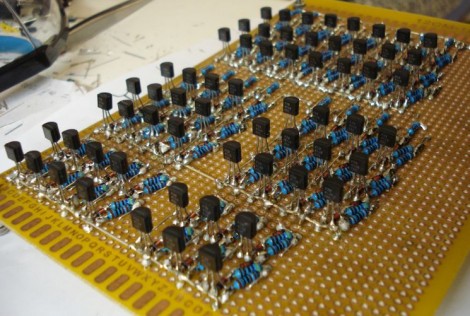

You’re going to want to do some stretching before undertaking a soldering project like this one. We’re betting that the physical toll of assembling this 4-bit discrete processor project is starting to drive [SV3ORA] just a bit crazy. This small piece of electronic real estate is playing host to 62 transistors so far, and he’s not done yet.

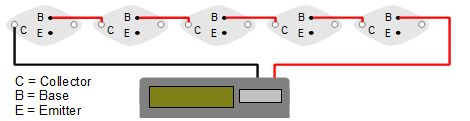

It’s one thing to build some logic gates in Minecraft (and then turn then into a huge 16-bit ALU). But it’s another thing to actually commit to a physical build. [SV3ORA] does a great job of showing the scope of the project by posting a tight shot of one inverter, then three in a row, then the entire 8-bit address and display system. These gates are built on the copper side of the board, with the power feed, LEDs for displays, and jumpers for control on the opposite side. We’re excited to see where he goes with this project!

But hey, if you don’t want to do that much soldering there’s a lot you can do on a few breadboards.

Recent Comments