We really like [Geert’s] take on accent lighting for his stairs. He built his own LED channels which mount under the bullnose of each step. The LED strips that he used are actually quite inexpensive. They are RGB versions, but the pixels are not individually addressable. This means that instead of having drivers integrated into the strip (usually those use SPI for color data) this strip just has a power rail and three ground rails for the colors. Ten meters of the strip cost him under forty dollars.

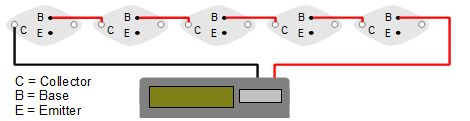

He did want to be able to address each step separately, as well as mix and match colors, so he designed the driver board seen above to use a set of TLC5940 LED drivers. These are controlled by the Arduino which handles color changing and animations. It will eventually include sensors to affect the LEDs as you walk up the stairs. Each strip is mounted in a piece of angle bracket, and they’re connected back to the driver board using telephone extension wire.

Recent Comments